Responsibility for maintenance of shared driveways

Disputes frequently arise between neighbours over a shared driveway. Those disputes often involve issues of excessive use by one party, access and parking within the driveway, and contributions towards maintenance of the driveway. This article focuses on the issue of maintenance of shared driveways.

Shared driveways

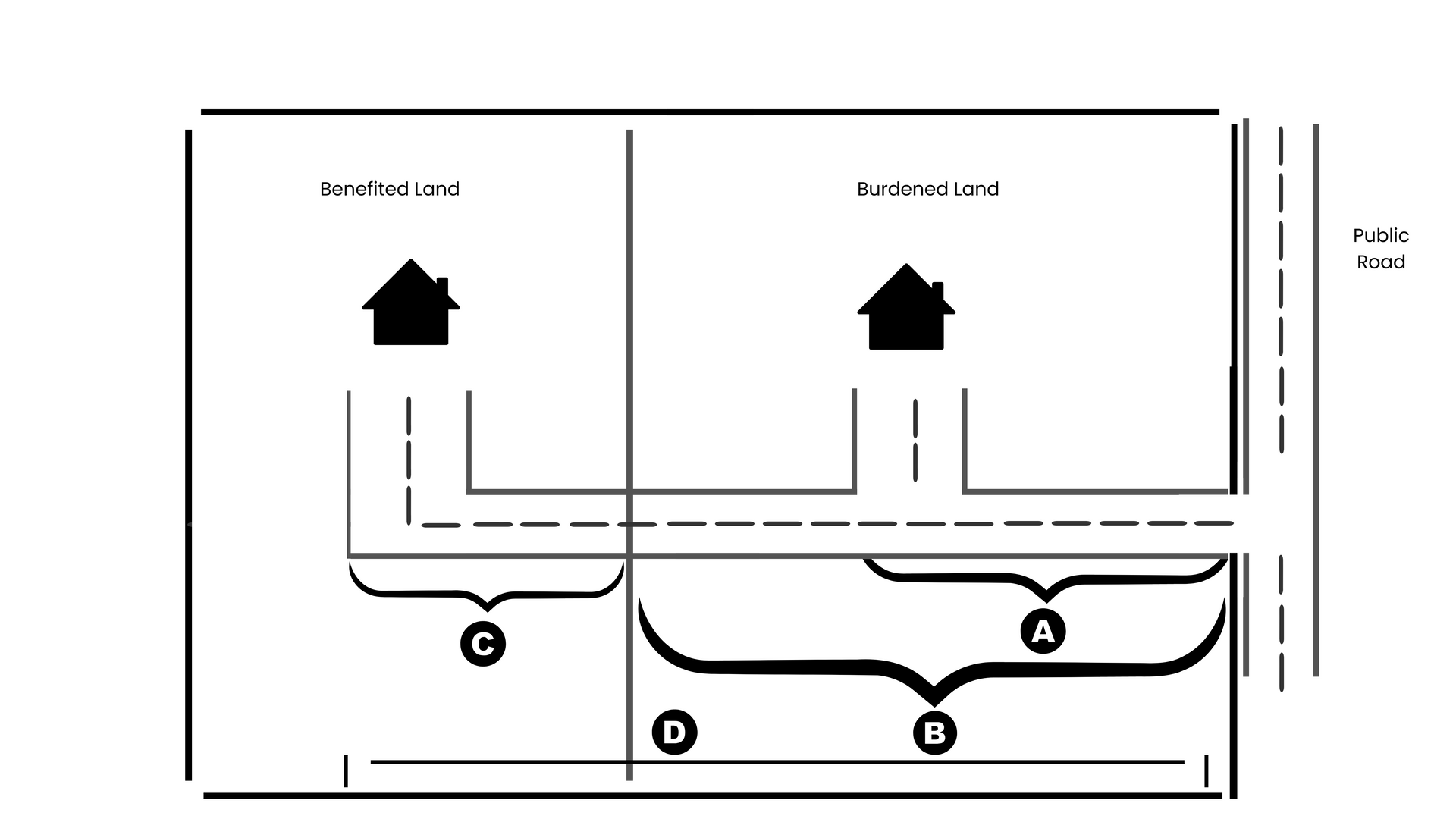

A common example of a shared driveway is where a right of carriageway passes through one neighbours’ (burdened) land into the other neighbour’s (benefited) land.

In the example above, the owner of the burdened land may argue that they should only maintain that part of the driveway they actually use (A).

The owner of the benefited land may argue that they should only be responsible for the part of the driveway on their land (C) and that the owner of the burdened land should be responsible for the whole of the driveway on its land (B).

But this argument by the benefited owner ignores the fact that the owner of the benefited land uses the entire length of the driveway to access the public road, including the part situated wholly on the burdened land (B).

So what is the legal position and who bears the responsibility to maintain? Surprisingly, there is no clear legal authority on this. Rather, we can glean some general principles from case law.

Owner of the burdened land not obliged to maintain

The starting position is that unless the terms of an easement dictate otherwise, an easement does not normally impose on the owner of the burdened land an obligation to repair or maintain the easement site: Jones v Price [1965] 2 QB 618.

Rather, the burden is a negative one, that is, the owner of the burdened land must not do anything that would obstruct or hinder the enjoyment of the easement.

If the owner of the benefited land wants to use the easement, it must do the work necessary to ensure the easement remains useable: Duncan v Louch (1845) 6 QB 904.

This is an illustration of the application of a dictum of Lord Mansfield in Taylor v Whitehead (1781) 99 ER 475 at 477 (KB), that he who has the use of a thing ought to repair it. The present law was explained by Salmond J in Spear v Rowlett (1924) 43 NZLR 801 at 803 as follows:

“The grant of an easement does not ordinarily and in itself impose upon the grantor any positive obligation to undertake upon his servient tenement any works, whether by way of repair, construction or otherwise, for the purpose of rendering that tenement fit for the exercise and enjoyment of the easement by the grantee. The obligation of the grantor is merely negative – an obligation, that is to say, to refrain from acts of misfeasance which obstruct the exercise of the grantee’s rights. It is for the grantee himself, at his own cost, to execute on the servient land such works as may be reasonably necessary for the exercise and enjoyment of the easement; and a right to enter and to do all such works is implied conferred on him by the grant without any express provision on that behalf.”

There appear to be two exceptions to the rule that the obligation to repair is on the dominant owner.

First, the servient owner may bind himself or herself by prescription to undertake repairs: Cameron v Dalgety (1920) 39 NZLR 155 at 162; Frater v Finlay (1968) 91 WN (NSW) 730 at 734 (DC).

Second, the servient owner may bind themselves to repair by express stipulation or by necessary implication: Miller v Hancock [1893] 2 QB 177 at 181 (CA); Cameron v Dalgety (1920) 39 NZLR 155 at 159-160.

Maintenance in the terms of the easement

The above common law position can be altered by terms within the easement prescribing responsibility for maintenance of the shared driveway.

Historically, courts would not enforce the terms of a positive obligation, (a positive covenant) as a right in rem binding successors in title: Austerberry v Corporation of Oldham (1885) 29 Ch D 750 (obligation to repair a road unenforceable against successors in title) and Rhone v Stephens [1994] 2 AC 310 (obligation to repair a roof projecting over adjoining cottage unenforceable).

In Rhone v Stephens [1994] 2AC 310 Lord Templeman said at 321:

“For over 100 years it has been clear and accepted law that equity will enforce negative covenants against freehold land but has no power to enforce positive covenants against successors in title of land. To enforce a positive covenant would be to enforce a personal obligation against a person who has not covenanted. To enforce negative covenants is only to treat land as subject to a restriction.”

For legal reasons, a successor in title could be bound by a negative covenant - that is an obligation not to do something, like damage an easement site. But, they could not be bound by a positive covenant - that is an obligation to do something, like maintain a shared driveway.

S 88BA Conveyancing Act 1919

Section 88BA of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (Conveyancing Act) resolves the above issue (see Aust-One Investment Pty Ltd v New World Investments Pty Ltd(18 February 2022) [2022] NSWSC 137; 20 BPR 42503 (Robb J) for commentary on the necessity and introduction of s88BA).

Section 88BA now provides for the imposition of positive covenants that require the maintenance or repair of an easement site. The covenant may be imposed on either the benefited land, or the burdened land (or both) provided that the covenant is imposed in the manner set out in the section.

88BA Positive covenants for maintenance or repair

(1) A covenant may be imposed requiring the maintenance or repair, or the maintenance and repair, of land that is the site of an easement or other land that is subject to the burden of the easement (or both) by any one or more of the persons from time to time having the benefit or burden of the easement.

[our emphasis]

Section 88BA was inserted into the Conveyancing Act in 1995 pursuant to the Property Legislation Amendment (Easements) Act 1995 (assented to on 12 December 1995).

The explanatory note to the Property Legislation Amendment (Easements) Bill 1995 provided:

Positive covenants for repair and maintenance

Under common law principles, it is not possible when creating an easement to include a covenant that will automatically impose positive obligations on successors in title each time land having the burden of the easement changes hands. Various devices have been used in an attempt to avoid the problem (such as imposing a contractual obligation requiring each person who disposes of such land to obtain a personal covenant from the next successor in title) but none has been found to be completely satisfactory.

Proposed section 88BA and consequential amendments to sections 87A and 88F will allow covenants that require repair or maintenance of the site of an easement to continue to apply after ownership of the land having the benefit or burden of the covenant changes.

Section 88BA of the Conveyancing Act recently arose in Barter v Theunissen [2024] NSWSC 326 in which Richmond J held that terms of an easement imposing an obligation on the owner of the servient tenement for the “maintenance and repair” of a rooftop terrace were preserved by operation of s 88BA.

The terms were:

“…(iv) in all other respects the owners of the servient tenement shall be responsible for the maintenance and repair of the roof of the servient tenement…”

Unfortunately, most rights of carriageway that create a shared driveway do not contain express terms prescribing responsibility for maintenance.

Typically, a right of carriageway registered over a shared driveway will simply use the words a “right of carriageway”.

By operation of s 181A of the Conveyancing Act, the use of the terms “Right of Carriageway” incorporates the standard terms in Part 1 of Sch 8 of the Conveyancing Act:

Part 1 Right of carriage way

Full and free right for every person who is at any time entitled to an estate or interest in possession in the land herein indicated as the dominant tenement or any part thereof with which the right shall be capable of enjoyment, and every person authorised by that person, to go, pass and repass at all times and for all purposes with or without animals or vehicles or both to and from the said dominant tenement or any such part thereof.

The standard terms do not prescribe responsibility for maintenance.

So that brings us back full circle to the common law principles regarding maintenance.

What happens where the terms of the easement are silent as to maintenance?

Clifford & Anor v Dove [2003] NSWSC 938 demonstrates the role of detailed easement terms in resolving disputes over shared driveway maintenance. It reinforces that servient owners must not hinder the enjoyment of easements, while dominant owners may be obligated to contribute to or initiate repairs, depending on the easement's terms.

A dominant owner is entitled to construct a road over the site of a right of carriageway: Newcomen v Coulson (1877) LR 5 Ch D 133, 143-4 (Jessel MR); Mills v Silver [1991] Ch 271, 286- 7 (Dillon LJ); Sertari Pty Ltd v Nirimba Developments Pty Ltd [2007] NSWCA 324, [9].

The right to construct a road or driveway is limited to that which is reasonably necessary for the effective and reasonable exercise and enjoyment of the easement: Zenere v Leate; Prospect County Council v Cross (1990) 21 NSWLR 601, 607-8 (Bryson J); Butler v Muddle.

The use of an easement by the dominant owner is subject to the concept of reasonable use. In Hare v van Brugge [2013] NSWCA 74 (Hare v van Brugge) Barrett JA (with whom Macfarlan JA and Tobias AJA agreed) considered the right to reasonable use of an easement at [25]-[26]:

“It may readily be accepted that a concept of reasonable use applies. But it applies to both parties. Each of them - the servient owner and the dominant owner - must exercise a degree of restraint in relation to an easement site. Neither may exercise his or her rights (the rights arising from the easement, in the case of the dominant owner, and the rights incidental to ownership of the burdened fee simple, in the case of the servient owner) in a way that interferes unreasonably with the enjoyment of the other's rights…All that obligations of reasonable use compel is that there should not be use inconsistent with the reasonable needs of the other party also to use the servient tenement.”

Both parties could, if they chose to, allow the shared driveway to fall into disrepair. Barrett JA said as much in Hare v van Brugge at [30]:

[30] In the circumstances of this case where Mr van Brugge and Mrs van Brugge, as the dominant owners, have, in relation to the easement site (including the part of it consisting of fixtures), the right to pass and repass created by the grant, their ancillary rights include the right to keep the fixtures in working order at their own expense. Mrs Hare, as the proprietor of the easement site (including its fixtures), has a corresponding right to keep the fixtures in working order at her expense. Each, therefore, is at liberty to maintain and repair the inclinator. Neither has that right to the exclusion of the other; nor is the right of one in some way superior to the right of the other. Also, however, neither party has any obligation in this respect. Each is quite free to allow the inclinator to be inoperative and to fall into disrepair and decay.

Hare v van Brugge concerned obligations to maintain a travelator. The court was not asked to consider whether the failure to maintain the travelator might render the dominant owner liable for nuisance or damage suffered by the servient owner.

In certain circumstances a dominant owner may be liable to a servient owner for nuisance and damage suffered as a result of failure to maintain drainage pipes within an easement: Comserv(No.1877) Pty Ltd v Wollongong City Council [2001] NSWSC 302 (Comserv). See also Jones v Pritchard (1908) Ch 630 per Parker J at 638-9 and Davies v Gold Coast City Council [2021] QDC 135.

In Comserv, Hodgson CJ (in Eq) stated that where the Council had resumed land for an easement, which land contained a pipe to carry storm water as the Council had a positive entitlement to cause water to flow through the pipe, that right carried with it the responsibility not to cause damage to the servient tenement by an unreasonable failure to maintain the pipe. That is, while there may not have been an express obligation to maintain, it was, in terms, a corollary to the avoidance of liability in nuisance.

Indeed in Comserv, the Chief Judge (in Eq) adopted Parker J’s view in Jones v Pritchard and stated at [50]:

“As a result of the easement, the Council now has a positive right to cause water to flow along the pipe; and in my opinion, that positive right carries with it a responsibility not to cause damage to the servient tenement by an unreasonable failure to maintain the pipe. In other words, in my opinion, the principle in Jones v Pritchard now applies.”

It follows that the positive right to pass along an easement may, in some circumstances, carry with it a responsibility not to cause a substantial and unreasonable interference with the servient owner’s use and enjoyment of its land, through failure to maintain that easement.

Conclusion

The terms of an easement are paramount.

Terms prescribing responsibility for maintenance of a shared driveway may be included within the easement. It is always important to have regard to the terms of the easement.

The common law position is that the owner of burdened land has an obligation to refrain from damaging a shared driveway - but not necessarily an obligation to maintain a shared driveway.

Historic case law tells us that the owner of benefited land must do that which is necessary to enjoy the benefits of the easement including maintaining a shared driveway.

However, if both parties share, and benefit from, a common driveway we can envisage circumstances in which a Court, in equity, finds that both parties must contribute equally towards maintenance.

Easements and disputes involving shared driveways can be complex.

If you are encountering these issues, we encourage you to book an initial consultation to discuss your particular circumstances.

Disclaimer

The contents of this article are a general guide and intended for educational purposes only. Determination of the types of issues discussed in this article is complex and often varies from case to case and involves an understanding of matters of fact and degree. Opinions on those matters can vary and be matters on which reasonable minds may differ.

DO NOT RELY ON THIS ARTICLE AS A SUBSTITUTE FOR COMPETENT LEGAL ADVICE.

Require further assistance? please do not hesitate to call us on (02) 9145 0900 or make an enquiry below:

Browse by categories

Servicing all of NSW, Whiteacre provides expert property law and planning and environment law advice and assistance.

✓ Planning Law Advice

✓ Land and Environment Court Appeals

✓ Voluntary Planning Agreements and Contributions

✓ Development Control Orders and Enforcement

✓ Property Development Advice and Due Diligence

✓ Title Structuring

✓ Easements and Covenants

✓

Strata and Community Title legislation

Book an initial consultation through our website with our planning law solicitor. Whether it's about planning and environment law or property law, you can approach us and discuss your matter to make sure we are a good fit for your requirements.