Tiny Homes, Caravans and Manufactured Homes in NSW Planning Law (Part 2)

In Part 1, we considered tiny homes and caravans on private land. That article can be accessed here Part 1. In Part 2, we turn our attention to tiny homes and manufactured homes.

Manufactured homes are generally constructed off-site and transported to a site where they are installed, either on a slab or on piers. Typically, but not always, they will be connected to existing stormwater and electrical infrastructure on the site. Tiny homes, kit homes, and modular homes can all be grouped under the definition of manufactured home if they share the traits of being self-sufficient, transported to a site as a whole or in major sections and fixed to the land.

The type of structure and degree of fixation to the land are important. Legislation in NSW makes a distinction, firstly between a structure on wheels and capable of being registered (a caravan) and a structure that is constructed in sections and installed permanently onsite (a manufactured home).

How are manufactured homes different from a traditional dwelling?

This question relates to the structure, not the use of the dwelling.

The legislation draws a distinction between something that is constructed mostly onsite (traditional dwelling - governed by the EPA Act) and something that is constructed mostly offsite and transported to the site in “major sections” (manufactured home - governed by the LG Act).

Development consent under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (EPA Act) is required for the construction of dwelling on a site, that is not a moveable dwelling. The EPA Act governs traditional structures and construction methods involving erection of a building onsite. Moveable dwellings are governed by the Local Government Act 1993 (LG Act), not the EPA Act. A caravan or a manufactured home falls under the definition of a moveable dwelling.

Let’s explore that distinction further.

Development consent is required under the EPA Act for “development”. Development is defined broadly in the EPA Act and includes the erection of a building:

1.5 Meaning of “development”

(cf previous s 4)

(1) For the purposes of this Act, development is any of the following—

(a) the use of land,

(b) the subdivision of land,

(c) the erection of a building,

(d) the carrying out of a work,

(e) the demolition of a building or work,

(f) any other act, matter or thing that may be controlled by an environmental planning instrument.

But what is a building you may ask?

The definition of “building” in the EPA Act is broad:

“building includes part of a building, and also includes any structure or part of a structure (including any temporary structure or part of a temporary structure), but does not include a manufactured home, moveable dwelling or associated structure within the meaning of the Local Government Act 1993.

There is extensive case law regarding what may be a “building” or a “structure” in planning law. If you are interested in this topic, you can read our article. [What is a “building” in planning law – and when is consent required?]

Importantly, the definition of “building” in the EPA Act excludes a manufactured home and a moveable dwelling as defined in the LG Act. This is why the distinction between a traditional building constructed onsite and a manufactured home transported to a site is important.

Let’s turn our attention to the definition of a manufactured home.

Manufactured Home

A manufactured home is defined in the LG Act as a:

“self-contained dwelling (that is, a dwelling that includes at least one kitchen, bathroom, bedroom and living area and that also includes toilet and laundry facilities), being a dwelling—

(a) that comprises one or more major sections, and

(b) that is not a motor vehicle, trailer or other registrable vehicle within the meaning of the Road Transport Act 2013,

and includes any associated structures that form part of the dwelling.”

A manufactured home must be a “dwelling”. There is a long history of case law concerning the definition of a “dwelling”. The use of the word in the definition requires that a manufactured home be intended for use as a domicile, or where someone lives permanently. Pepper J summarised and reviewed the case law on this issue in Dobrohotoff v Bennic [2013] NSWLEC 61.

Her Honour stated at [45]:

“Furthermore, when considering the first limb of the definition of "dwelling", regard must be had to the notion of "domicile" contained within it (820 Cawdor Road at [24]), and the critical element of permanence. Inherent within the term "domicile" is, as a long line of authority in this jurisdiction has established, the notion of a permanent home or, at the very least, a significant degree of permanence of habitation or occupancy…”

Secondly, the manufactured home must be a “self-contained” dwelling containing a bedroom, living room, kitchen, bathroom and laundry. Sometimes, in a studio arrangement, these will all be contained in a single space.

Thirdly, a manufactured home must “comprise one or more major sections”. This picks up the idea that a manufactured home is manufactured offsite and may arrive as a complete unit or in sections that are installed onsite.

Finally, a manufactured home must not be a motor vehicle, trailer or other registrable vehicle. This excludes campers, trailers and importantly, caravans from the definition of a manufactured home.

What is required to install a tiny home or manufactured home onsite?

Generally, two things will be required. First, an application under s 68 of the LG Act will be required to install the manufactured home on a site and connect into services like power, water and sewage. Secondly, development consent may be required for the use of the manufactured home as either a home office or secondary dwelling.

Installation of the manufactured home is governed by the LG Act, not the EPA Act.

Section 68 of the LG Act specifies the “activities” that require the approval of council. One of those “activities” is the installation of a manufactured home, moveable dwelling or associated structure on land. Other “activities” for the purposes of section 68 are carrying out water supply connections, carrying out sewerage work and stormwater drainage work. So, a section 68 approval is required for the installation of a tiny home or a manufactured home and (usually) water supply, sewerage and stormwater work.

In addition, development consent for use of the manufactured home will be required. This can either be in the form of an application for development consent to Council, or in some circumstances, to a private certifier as complying development. It will save time and cost to make both the s 68 application and the development application at the same time.

A competent town planner should be engaged to clarify what is required to accompany each application and to assist with managing the various consultants and any reports that are required.

So that deals with the installation of a manufactured home. But what about its use?

Physical structures vs use

The installation or construction of a structure is one thing, the use of that thing in planning law is another. This is best illustrated through an example. A manufactured home might be installed on a site for use as a home office or granny flat (in planning law a “dwelling”). Following installation, the granny flat might be used to house an aging parent or a university student. The

structure is a slab, four walls and a roof. But the same structure can be put to many different uses. After the aging parent or university student moves out (hallelujah) that same granny flat could be converted into backyard commercial pub. Same building, same structure, vastly different use (and impact on the neighbours). This is an extreme example, but it highlights the distinction between a structure and its use.

So it may be lawful to ship a manufactured home to a site and install it onsite, but consent may still be required for the proposed use of the manufactured home on the site. Before installing the manufactured home onsite, the first question to consider is the zoning and whether the proposed use is permissible within the relevant zone.

Zoning

Almost all land in NSW has a specific zoning, for example R2: Low Density Residential zoning or RU1: Primary Production.

The zoning of a site can be easily obtained through NSW government websites (https://www.planningportal.nsw.gov.au/spatialviewer).

Once the zoning has been obtained and understood, we can look to the relevant Local Environmental Plan for the “land use table” relevant to the zoning.

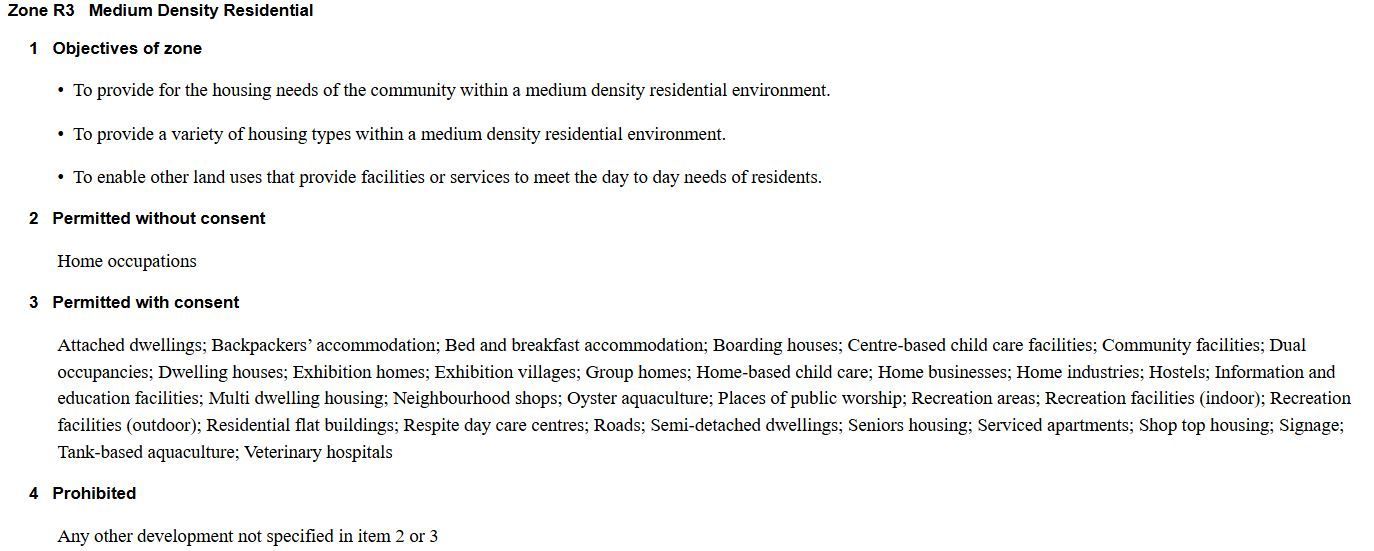

Land use tables look like this:

The “land use table” for a specific zone will describe a number of land uses that are:

(i) permitted without consent

(ii) permitted with consent; and

(iii) prohibited.

We can see in the above land use table that dual occupancies and dwelling houses are permissible in the zone (with consent). Any use that falls outside “permitted without consent” or “permissible with consent” is prohibited in the zone.

To determine which of these three categories the proposed use falls into, we must first define the use.

How do we properly define the use?

Tiny homes or manufactured homes installed on a site will typically be used as a “secondary dwelling” which is defined in the LEP as “a self-contained dwelling that is established in conjunction with a principal dwelling.” A granny flat would be permissible (with consent) in the above R3 Medium Density Residential zoning because it could fall under the definition of “multi dwelling housing” which is defined in the LEP as “3 or more dwellings (whether attached or detached) on one lot of land, each with access at ground level.”

Characterisation of use can get quite complex but we don’t need to go into that detail in this article. If you are interested in this topic, you can read our article at [Characterisation of Use in Planning Law].

Recall our two examples above. If the same granny flat is to be used as a dwelling, the use is permissible (with consent) in the R3 zone but the use of the granny flat as a commercial pub (food and drink premises) is prohibited in the zone.

Conclusion

The installation and use of a manufactured home on a site should be relatively straightforward. But, it pays to engage a competent town planner to check the site, the proposed use and the zoning before proceeding to ensure the installation and use are permissible on the chosen site.

This article considered the installation of tiny homes and manufactured homes on private land in NSW. Part 1 of this article examined tiny homes and caravans and can be accessed here: Part 1

Disclaimer

The contents of this article are a general guide and intended for educational purposes only. Determination of the types of issues discussed in this article is complex and often varies from case to case and involves an understanding of matters of fact and degree. Opinions on those matters can vary and be matters on which reasonable minds may differ.

DO NOT RELY ON THIS ARTICLE AS A SUBSTITUTE FOR COMPETENT LEGAL ADVICE.

Require further Assistance? Please do not hesitate to call us on (02) 9145 0900 or make an enquiry below.

Browse by categories

Servicing all of NSW, Whiteacre provides expert property law and planning and environment law advice and assistance.

✓ Planning Law Advice

✓ Land and Environment Court Appeals

✓ Voluntary Planning Agreements and Contributions

✓ Development Control Orders and Enforcement

✓ Property Development Advice and Due Diligence

✓ Title Structuring

✓ Easements and Covenants

✓

Strata and Community Title legislation

Book an initial consultation through our website with our planning law solicitor. Whether it's about planning and environment law or property law, you can approach us and discuss your matter to make sure we are a good fit for your requirements.